Kenny Wheeler: Profile of an Incredible Career

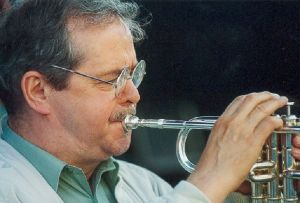

Still a prolific performer and composer into his eighties, Kenny Wheeler is among the most influential trumpet players in jazz. The Festival of New Trumpet Music is proud to present Kenny Wheeler in a four-concert series taking place October 20 through 23, where he will appear with some of New York’s most in-demand trumpet players, including Ingrid Jensen, Jonathon Finlayson, Shane Endsley and Nate Wooley and the John Hollenbeck Large Ensemble to perform a range of his classic and new compositions for large and small jazz ensembles and brass ensemble.

Kenny Wheeler is a musician about whom very much can be said, and it still might not be enough. Wheeler has changed the fields of jazz improvisation, free improvisation and jazz composition, and has created a vast body of work that, judging from its diversity, quality and creativity, would look like it had been achieved by five musicians and not just one. Dave Holland, who will join Kenny Wheeler at the Jazz Standard on October 25, had this to say about Kenny on his blog:

As you travel your musical path you meet certain musicians who play a significant role in shaping your understanding of musical possibilities. I was lucky enough to meet Kenny early in my life and his work as a composer and player has been a source of inspiration since then. – Dave Holland

On top of all this, Kenny Wheeler is regarded as one of the kindest human beings around who is remembered fondly by all who cross his path. Though he never would have asked for it because of his legendary shyness, the Festival of New Trumpet Music is proud to honor Kenny Wheeler for all of his accomplishments in music and trumpet playing, and to recognize his important work as an artistic citizen of international significance. Following is a brief survey of Kenny Wheeler’s career intended to provide some context for his rare visit to New York City, and to introduce the broad range of his work to those who may be unfamiliar.

Born in Toronto, Canada in 1930, Kenny Wheeler was introduced to music through his father, an amateur trombonist. Beginning with Dixieland and Big Band music, Wheeler eventually began to aspire to play bebop, through a meeting with a group of friends where he first heard Dizzy Gillespie when he was fifteen. As Wheeler became more familiar with a music he disliked at first, Gillespie and bebop eventually became major influences, and jazz became his primary interest even as he earned his living playing commercial music in London.

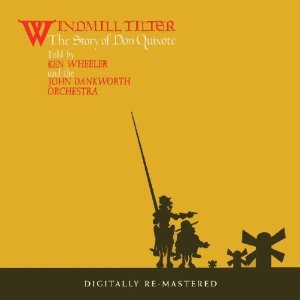

After some formal music study in Montreal, Wheeler moved to London, and he eventually joined the John Dankworth Orchestra for a date at the Newport Jazz Festival, and later as a regular member. Wheeler began composing for the band and, during some time off from playing due to complications from wisdom teeth surgery, Dankworth suggested he write an album for the band. Wheeler’s first album as a leader, Windmill Tilter, a suite of music based on Don Quixote recorded in 1968, was the result. The album was for some time a collector’s item due to the original master tapes being lost, but was reissued in 2010 and stands as an important album in the big band tradition that began to establish Wheeler’s reputation as an important writer and player. Already Wheeler’s signature penchant for lush orchestration, dark-hued melodies and free-ranging improvisations were already apparent as a composer, and his unmistakable sound as a trumpet player had taken shape.

In a 2002 interview on ArtistHouseMusic.org Wheeler says that even though he loved bebop, he “could never do it, even though it was my root.” It was partly this frustration with bebop that led Wheeler into his association with free jazz that marked a significant new chapter of his musical life. Wheeler began to hear about a new music that was being formulated in some London clubs, and went to hear it himself. At first he didn’t like it, but eventually he sat in and, as he said, “went berserk on the trumpet for about ten minutes.” Wheeler later became a major player on the European free jazz scene, working with the Globe Unity Orchestra, Spontaneous Music Orchestra and Evan Parker, among others. Wheeler’s association with Anthony Braxton, from 1971 through 1976, was also a significant time for him, where his technical skill on the trumpet and free approach to improvisation made him one of few trumpet players suited to Braxton’s often difficult compositions.

Nick Smart, a trumpeter and educator at the Royal Academy of Music in London as well as a close associate of Wheeler’s, said in a interview that Wheeler considered his playing “at its best when he was doing equal amounts of free playing and conventional playing.” Smart also mentions that the trumpeter Booker Little was a very significant influence on Wheeler. In an interview Smart conducted, Wheeler mentions that hearing Booker Little’s music “opened a new door” for him. For someone for whom courage was perhaps in short supply in the early years of his career, Little’s example provided a source for the “courage to go his own way” in his music, marrying together a unique, non-standard approach to sound on the trumpet with the bebop tradition. Kenny Wheeler developed his own approach to this idea, and his influence has passed on to many of today’s trumpet players where his influence serves them today, as Nick Smart said, as Little’s once did to Wheeler.

Wheeler’s involvement with free improvisation changed things for him, even though even many years later he says, in typical Kenny Wheeler style, that he is still unable to say whether or not he felt the music was good or bad. Most importantly though, he did feel the style allowed him to “get something out” that he couldn’t before. About the large ensemble free jazz projects he was involved in like the Globe Unity Orchestra, he said that they were “good experiences” but that he had to “fight to really get a solo.” In this statement Wheeler reveals his interest in the solo, lyric voice within the ensemble context that is a fundamental element of his music.

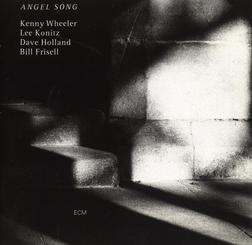

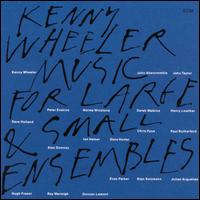

Wheeler’s compositions for large ensemble, the most well-known of which are those recorded on Music for Large and Small Ensembles on ECM records from 1990. Wheeler cites Duke Ellington and Stan Kenton as a major influence in his own large ensemble music, as well as Debussy, Hindemith, Ravel and Bartok. As far as what he’s actually trying to do, Wheeler is more likely to say that he likes to “find soppy romantic melodies mixed with a bit of chaos” or that he “writes pretty songs and joins them up” than to give a detailed, technical analysis of his own music. The music itself is much more than Kenny’s words might indicate. The first moments of “Seal Lady” beginning with Evan Parker’s solo introduction with its abstracted sounds soon joined by the lush sounds of the winds, eventually giving way to an expansive statement from Wheeler’s flugelhorn, and then Norma Winstone’s hushed, poised singing, are among the most striking and beautiful moments ever recorded. Just the first three minutes of this piece, not to mention the entire piece and the entire album, show most of the many faces of Wheeler’s artistic vision, where so much of modern music comes together into a single, sophisticated statement.

In a particularly fertile period, 1975 through 1978, Wheeler recorded with Anthony Braxton, his trio Azimuth with Norma Winstone and John Taylor, the Globe Unity Orchestra and released both Gnu High and Deer Wan on ECM, two records that cemented Wheeler’s status as an important player in Europe, and beyond. On display here is not only Wheeler’s productivity, but also his diversity as a player and composer. Wheeler was one of the first jazz musicians to integrate western classical music, jazz and free improvisation into a complete, compelling and unique style. Beginning with Windmill Tilter and continuing through his most recent recordings, including 2008’s Other People with the Hugo Wolf String Quartet and his newest music for big band, Wheeler’s breadth of interests and skill at transcending them to create a personal music, have set a new standard for trumpet players and musicians who have followed.

Wheeler’s upcoming residency in New York will go a long way to show just how that influence has manifested itself in some of New York’s most active trumpet players and composers and to honor this incredible musician’s contributions to the art.

Douglas Detrick is a trumpeter, composer, and music writer based in New York City. Having worked as a composer and performer in jazz, chamber, improvised, and electro-acoustic music, he is interested in the intersection of these forms and their resonance with our culture. Detrick has written for NewMusicBox, About.com, and for his own blog at douglasdetrick.com.

For further reading:

http://www.artistshousemusic.org/videos/kenny+wheeler+interview – video interview from 2002

http://www.daveholland.com/blog/kenny-wheeler – Dave Holland writes about Kenny Wheeler

http://jazztimes.com/articles/20565-kenny-wheeler-slowly-but-surely – Gene Lees, an early friend of Wheeler’s, writes about their time together in Canada.

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=993&pg=1 – 2003 interview by John Eyles

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2010/oct/14/kenny-wheeler-interview – article on Kenny Wheeler by John Fordham