Bill Dixon died in his sleep last night, at his home in Vermont. The news has spread fast, partly a testament to the strength of Bill’s legacy, and partly an example of the hyper-media age we live in, a strange contrast to the timelessness and infinite patience of his music.

I wanted to offer a short remembrance, along with posting a few recent articles I’ve written on Bill’s work: the liner notes to the recent Tapestries for Small Orchestra recording, and an appreciation upon the 25th anniversary of his November 1981 album. As my own blog is on hiatus, I thank Darcy James Argue and the Festival of New Trumpet for letting me use their platforms for my words. – Taylor Ho Bynum

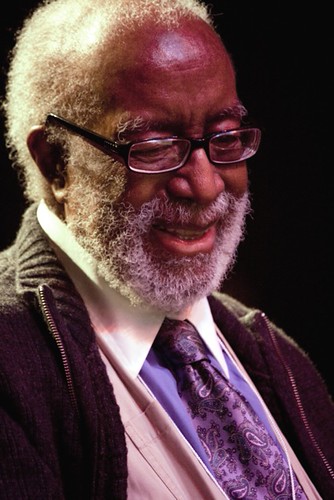

BILL DIXON, 1925-2010

June 17, 2010

I got the news at 9am this morning from Stephen Haynes, my friend, my brother in brass, and the man who introduced me to Bill a little over a decade ago. A little later in the day, I talked to Sharon Vogel, Bill’s life-partner. She has been an amazing presence in Bill’s life, loving and committed to the music and as iron-willed as the maestro. My thoughts and love to her, and there is great comfort knowing Bill’s legacy is in such strong hands.

I visited Bill just last Friday, and it was obvious this day was coming soon, but it is still hard to process. I spent a few hours by his bedside. I played him the pocket cornet I had just received as a gift from our friend Michel Cote. I read him passages from a new book, I Want To Be Ready: Improvised Dance as a Practice of Freedom, by my friend Danielle Goldman, that includes a fantastic chapter on the important and grossly under-recognized interdisciplinary partnership between Bill and dancer/choreographer Judith Dunn in the ‘60s and ‘70s. (When asked by Goldman why there is not more discussion of their collaboration, Bill offered the classic quote “The history that gets written is the history that’s permissible.” I’m glad he lived to see scholars like Goldman, Andrew Raffo Dewar, Ben Young, and others, establish the standard for a new and deeper level of documentation.)

He also quizzed me about what projects I was working on, and we discussed plans for releasing the concert recording of the performance we had done at the Victoriaville festival two weeks prior. Even in a weakened state, he was engaged in the work.

It’s hard to believe the Victoriaville concert was only three weeks ago. We had been invited to reconvene the ensemble that recorded Tapestries for Small Orchestra in the summer of 2008: Bill, Graham Haynes, Stephen Haynes, Rob Mazurek, Glynis Lomon, Michel Cote, Ken Filiano, Warren Smith, and myself. It was one of the most intense musical weekends I’ve ever experienced. Bill had composed all new music for the occasion. It was clear Bill was fighting for the strength to make it happen, and we all understood the stakes. In his life, he could be demanding, because he refused to compromise the quality of the sound he was always searching for. And he was still pushing us hard in that last rehearsal. Stephen and I quietly shared a smile when he chastised the trumpets for an unconvincing entrance; Bill was definitely still with us! He was telling stories, he was dropping wisdom in his inimitable fashion, he was challenging us to play something new. At one point he said, “You know, they might drop the bomb tomorrow, and this will be the last concert for all of us. Play like it matters!”

When Bill arrived at the soundcheck, after we had set-up and gotten all the basic levels, he took command of the stage. The immediate strength of his presence erased any doubts or concerns we might have had about his ability to make it through the night. The concert was powerful, Bill conducting us through the material, drawing the music out of the band. At the end, Bill took to his feet, gesturing for the brass section to reach beyond what we thought we had left in a final burst of musical intensity. After the show, Bill was full of life backstage, thanking us all for the music, receiving our profound gratitude in return.

It is so hard to lose someone like that. As a facebook post I saw this morning said “I thought Bill would outlive the planet!” His achievements were extraordinary, as all the obituaries that will come out in the next few days will attest. His legacy is enduring, as all of us fighting for that one true sound continue the journey. And he made it through 85 years, making vibrant, beautiful, world-changing music up until the very end, and what more could you ask for.

When I said goodbye last week at his home, I told him I’d try to visit him again in a few weeks, but I knew that was unlikely. I wish I had the guts to really say goodbye, to tell him how much his music changed me, changed so many of us. To tell him I loved him and would never forget what he taught me. But I like to think he knew.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

BILL DIXON: The Essence of a Sound and the Infinity of a Moment

(Liner notes to Tapestries for Small Orchestra, Fall 2009)

The music of Bill Dixon maintains such a powerful flavor, it is one of those things where you inevitably remember the first time you taste it. For me, it was his mid-career landmark recording November 1981. Within the one minute and twenty six seconds of Webern, the opening track, I realized I had to completely rethink the possibilities of the trumpet as an improvising instrument. By the end of the album, I realized I had to examine my assumptions about the nature of creative music in general. For Dixon’s music does not adhere to the common practice of any established musical genre, be it “jazz”, “contemporary classical”, “avant-garde”, or what-have-you. While drawing upon all of these rich traditions and more, he has established his own set of rules and principles, creating a wholly individualistic canon over the course of his extraordinary career.

Bill Dixon came to music relatively late in life, in his early twenties, after training as a visual artist. From the beginning, Dixon had an advanced sense of what he wanted to accomplish in the medium, doggedly pursuing his own interests rather than following the paths others might prescribe for a more traditional student. In the ensuing 60 years, these instincts have naturally evolved and been consciously refined into an inimitable sound world. At an age where some artists might coast on a lifetime of accomplishments, Dixon’s work continues unabated and with unceasing vibrancy; the last few years have seen the exceptional orchestral recordings of Exploding Star Orchestra and 17 Musicians in Search of a Sound: Darfur. This activity culminates in Tapestries for Small Orchestra, with two hours of music and a documentary film culled from a multi-day residency with a handpicked mid-sized ensemble at the Firehouse 12 Studios in New Haven CT.

One of the exciting aspects of Tapestries is the insight it allows into Dixon’s process and the way it illuminates core structures of Dixon’s musical DNA. Ever since that first, sharp bite of November 1981 years ago, I have endeavored to gain some understanding of his music. After years of focused listening, a treasured handful of performance opportunities, and occasional conversations with the maestro, participation in this project clarified some of my rough impressions to the extent that I feel comfortable articulating them. Of course this just scratches the surface; I would recommend the interested listener search out the more detailed and scholarly research of Andrew Raffo Dewar, Ben Young, and Stanley Zappa, among many others, in addition to reading Dixon’s own writings.

There is a revealing moment in the documentary where Dixon discusses his frustration with composition teachers insisting one must never double the third. He was dissatisfied with traditional pedagogy presenting rules without taking the time to explain why. Dixon took the time to learn the “rules” of traditional music-making (in fact, he spent five years in conservatory study). However, he also learned to reject dogma that impeded the trajectory of his personal creative journey. He went on to discover doubling the third produces “one of the most beautiful sounds in music,” but it is so strong it changes the nature of the chord. For his own music, Dixon was not interested in the functionality of the harmony; he cared about what kind of sound that assemblage of notes created, not what it was supposed to lead to.

The most celebrated musical breakthroughs of the 20th century, from Schoenberg to Parker, tended to involve harmonic innovations. (Not coincidentally, also the easiest concepts for institutions to promulgate through the kind of simplistic definitions Dixon rebelled against.) Even amongst Dixon’s peers in the early 1960s like Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, and Albert Ayler, the effort to explore, subvert, or explode harmonic conventions remained a primary motivation. However, for Dixon, pushing against the constraints of harmony never seemed to be a motivating factor; instead, his consistent mission seemed to be asserting the primacy of sound itself.

In much of Dixon’s music, vertical harmony is not about moving towards (or away from) any tonal resolution, but about a distinct sonic experience existing in its own space and time. So much music is about “getting somewhere;” from the basic principles of the sonata form to impassioned free jazz improvisations leading to inevitable climaxes. But Dixon was unusual among his ‘60s contemporaries for avoiding this need for forward momentum; rather, he stops the clock, and turns his gaze inwards, towards the infinite potential of the existing moment, rather than the moment to come. His music acts like a microscope of time, peering in at the atoms of a suspended cell and the universe of activity contained therein. This sense of timelessness has always been one of his hallmarks, and allows him to explore the extremes of duration like few other artists. Dixon’s compositions might be thirty seconds or thirty minutes, but the seconds last an infinity, and the half-hour passes in a single breath.

Listen to the album’s title track, Tapestries, as an example. While the low-end instruments (cello, contrabass clarinet, acoustic bass) bubble with ceaseless motion, the brass remains wholly unperturbed, resounding slowly evolving harmonic clusters. (It is somewhat reminiscent of Charles Ives’ Unanswered Question, another revolutionary American master who managed to capture the feeling of eternity.) Again, where free jazz cliché would draw the horns into the temptations of the rhythmic excitement, Dixon holds them back, creating an exquisite tension that lasts throughout the composition.

In the past, some of Dixon’s large-ensemble works have involved extensive, traditionally styled, written notation (his talents as an arranger and orchestrator, as demonstrated on the 1966 classic Intents and Purposes, are too rarely acknowledged). However, Dixon considers all forms of information exchange as a kind of notation, understanding that new musical ideas may need similarly new means of expression. So in recent years, Dixon has gone in a different direction; he will bring in a minimal amount of materials, but painstakingly craft how those materials are played and interpreted. The process becomes the notation. In rehearsal, it is not unusual to spend an hour on how a single line is phrased, or how a solitary chord resonates. By applying this level of care to the smallest details, Dixon forces the performers to become deeply aware of and engaged in every sound they create, and how the choices they make as individuals effect the ensemble as a whole. There also are a few pieces on Tapestries that had no written materials or instruction, but they are far from “free improvisations;” by existing in the sonic environment he cultivated and adhering to the clear principles he provided, the results are unmistakably the music of Bill Dixon.

Just as it is impossible to distinguish between the moments of composition and improvisation, it is a false dichotomy to distinguish between Dixon’s identity as composer and instrumentalist. In Dixon’s music, these are simply terms for the various practices of a consistent artistic vision. But this vision is clearly delineated in his innovations as a trumpeter. For all the extended techniques he has pioneered and the virtuosity he has displayed over the years, Dixon’s most striking tools have always been the diversity of his timbral palette, the character of his tone, and the drama of his rhythmic phrasing and use of space. From his earliest recorded improvisations with Archie Shepp and Cecil Taylor to the material in this package, it has always been less about the notes he plays than the sounds he chooses and where he places them. Where some trumpet players sorely miss the pyrotechnics of youth as they get older, Dixon’s playing maintains its intensity. While the physical palette he draws from has changed with age, the mastery with which he wields the brush continues to flourish. Take the openings of Tapestries’ two trio pieces, Slivers: Sand Dance for Sophia and Allusions I. What other trumpeter could shatter the silence with that kind of authority?

Dixon’s influence on the subsequent generations of brass improvisers is profound. The trumpet and cornet players on this album (Graham Haynes, Stephen Haynes, Rob Mazurek, and myself) are but a few examples of his many musical progeny, and even amongst the four of us, the diversity of ways this influence manifests itself is striking. None of us sound alike, nor do we sound like Dixon, but all of us clearly draw upon Dixon’s legacy in how we approach our horns. (It is also interesting to note that three of us are almost exclusively cornet players, and the fourth a very frequent practitioner. While perhaps less accurate and aggressive than the trumpet, the cornet has greater timbral flexibility; it is an instrument for those who improvise with sound as much as with notes. Not a coincidence that we are all so attracted to Dixon’s music.)

This influence is by no means restricted to brass players. Dixon’s subterranean explorations in the depths of the trumpet register clearly offer a template for Michel Coté’s contrabass clarinet work. Glynnis Lomon’s cello recontextualizes the rough-edged beauty of Dixon’s sound, where resonant pedal tones alternate with thrilling harmonics. Bassist Ken Filiano met Dixon for the first time at this recording, while the masterful percussionist Warren Smith has known him for over forty years, but both demonstrate an intrinsic understanding of his concepts. They allow the music enough space to breath freely without sacrificing rhythmic intensity.

For those who are already familiar with Dixon’s music, this recording offers a bracingly fresh document from an artist who, like Ellington or Picasso, refuses to sit still even after a fifty-year career. It is one moment in a journey of uncompromised expression investigating the very principles of sound. For those approaching Dixon’s music for the first time, I envy you. Hopefully, Tapestries for Small Orchestra will be the first addictive taste, offering a sonic feast to those open to experiencing sound and time in a new way.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Dixon: November 1981 at 25

Posted on SpiderMonkey Stories, November 28, 2006

One of the inspirations I had in starting this blog was the recent online discussion of great albums recorded in the period between 1973 and 1990, initiated by posts by Dave Douglas and Ethan Iverson, with the many contributions compiled at www.behearer.com. For me, this was a great example of the potential of online discourse. Musicians, writers, and fans used the resources of all this new-fangled communication technology to address a period of music grossly and unjustly neglected by the mainstream music media, create an intelligent and informed discussion on that music, and provide a starting point for new listeners to explore some truly innovative and ignored work. And, of course, it provided a forum for slightly obsessive fanatics like myself to voice their opinions on essential recordings from the past thirty-plus years. Having come to the blog world too late to participate in that discussion, I cannot resist using this space to discuss one of my all-time favorites, presently celebrating its 25th anniversary (that was missed in the ‘73-90 discussion!), Bill Dixon’s November 1981.

I didn’t check out Dixon until relatively late in my musical education, when I was about 19 or 20. I had certainly heard his name referenced by mentors and teachers of mine, but his relatively few recordings were harder to access than the copious catalogs of Miles Davis, or Lee Morgan, or even Lester Bowie, who was my major “avant-garde” influence at that point. But I had definitely started to explore post-‘60s improvisational styles in my own playing, so after people kept saying I must be influenced by Dixon, I realized I was overdue for some research into his music.

So I picked up November 1981. (Probably just because that was the one title Tower Records (rest in peace) had in stock at the moment. And I thought he had an extremely hip hat on the cover photo.) And I took it home, put it on my stereo, and within the one minute and twenty six seconds of the opening solo trumpet track (Webern), I realized that I had to completely rethink the possibilities of the trumpet as an improvising instrument. For me, November 1981 counts in the small handful of recordings that gave me truly revelatory listening experiences. (The short list would include Miles’ In a Silent Way, Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, and Jimi’s 1983…(A Merman I Should Turn To Be) (at fifteen years old, those were the records that made me want to become a musician), and maybe Beethoven’s Egmont Overture and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, with Mingus’ Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, Threadgill’s Too Much Sugar for a Dime, Braxton’s Willisau Quartet, Ives’ Holidays Symphony, Ellington’s Far East Suite, Bartok’s String Quartets, and Prince’s Sign ‘O’ The Times probably rounding out the personal pantheon. This is not necessarily a list of my favorite records, (though they’d all probably count in that category as well), but a list of the records that just got to me at the right time, that changed me, or the way I approach music, in a fundamental way in my teens and early twenties.) And of all these records, November 1981 probably was the most specifically influential upon me as an instrumentalist. While I certainly hope my own playing, particularly since I switched to cornet, does not explicitly copy Dixon’s approach, I must acknowledge the way his sound (along with Don Cherry, Wadada Leo Smith, etc) expanded the basic palette and vocabulary available to any modern improvising brass musician.

At this point, now that I’ve dug deeply into Dixon’s discography, it would be hard for me to name a single favorite record. The ‘60s recordings, both with Archie Shepp and Intents and Purposes, are wonderful documents of Dixon’s unique and individual take on that remarkable historical period in the New York music scene. (This is right around when Dixon founded the Jazz Composer’s Guild and organized the October Revolution of 1964, when Coltrane was taking it out, Sun Ra was taking it outer (space, that is), the New York Contemporary Five and the New York Art Quartet were formed, etc. A heavy time in the City! And Dixon’s playing on Cecil Taylor’s Conquistador, so good.) Then Odyssey, his self-released 6-CD box set of solo recordings, mostly from the ‘70s, shows the development of his music in the relative isolation of Bennington, Vermont. Dixon’s stated goal was to play with the full timbral, dynamic, and register range of an orchestra on a solo trumpet, and impossibly, he succeeds. For me, these recordings set the standard for the trumpet as a solo instrument, and provide one of the most radical reimaginings of the instrument in the past fifty years. (Not released until 2001, this set also filled in the historical question of what Dixon was up to in the ’70s, and illustrated the practice of instrumental investigation that the extraordinary techniques evident on November 1981 came out of.) Then in 1980, Dixon reemerged on the scene with a series of great ensemble recordings on the Soul Note label, starting with the two volume In Italy records (with the three trumpet frontline, with my man Stephen Haynes) and continuing through the ‘90s. They’re all good, but In Italy, November 1981, the two volume Vade Mecum, and the two volume Papyrus (duos with Tony Oxley, I’m a sucker for the drum/trumpet duo) are my favorites. And the more recent recordings are powerful, Berlin Abbozzi on FMP and the trio with Cecil Taylor and Oxley on Victo. (This last record has caused some critical controversy, but I love it. Dixon gets Cecil to enter his musical world, and Cecil responds with some of his most spacious and lyrical playing on record.)

But with all that, I still think November 1981 serves as the perfect starting point. This is partly for sentimental reasons, since it was my first Dixon record, but it is an essential mid-career statement, the first recording where Dixon applies all of the new techniques and ideas of his individual musical practice of the ’70’s as the sole horn in an ensemble setting. It’s a great band, with Mario Pavone and Alan Silva on bass, and the under-heralded Laurence Cook on drums (a legendary figure on the Boston scene when I was living there, a real character, and one of the lightest dancing cymbal touches I’ve ever heard, along with a totally wild improvisational energy.) The album effortlessly moves from intense, sound-oriented timbral improvisation to gorgeous, breathtaking lyricism, from bubbling, rhythmic two-bass energy to magical moments of droning, suspended time. It perfectly balances many of the contrasts that Dixon has been dealing with throughout his career. It sounds completely improvised, yet wholly composed; it has moments of shock and beauty, time and no-time, harmony and freedom.

My friend, scholar and soprano saxophonist Andrew Raffo Dewar, wrote an outstanding master’s thesis on Dixon’s work, including an in-depth analysis of Dixon’s composition Webern, the solo trumpet piece that opens November 1981 and first blew my mind. (Hopefully some or all of it will be published soon; in the meantime, the academically connected might be able to get a copy from Wesleyan University through inter-library loan.) And with Mr. Dixon’s gracious permission, tonight (Nov. 28) in a gig at the Stone, my trio (with Mary Halvorson and Tomas Fujiwara) will be performing our interpretation of some of the material from this album, in honor of its 25th anniversary, along with some original compositions of mine. And whenever you get a chance, you should try and catch one of Bill Dixon’s too-rare live performances. I saw a marvelous duo with George Lewis at this year’s Vision Festival. As Bill has gotten older, his playing has gotten more refined, as he’s moved from some of the pyrotechnics of his playing in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s to a deep exploration of sound and silence in the mid and lower register. His sense of pacing and musical drama is subtle and profound, and the combination with Lewis’ electronic manipulations and trombone virtuosity was absolutely beautiful.